October 27, 2013

These pieces will be on display in a gallery space at the shows:

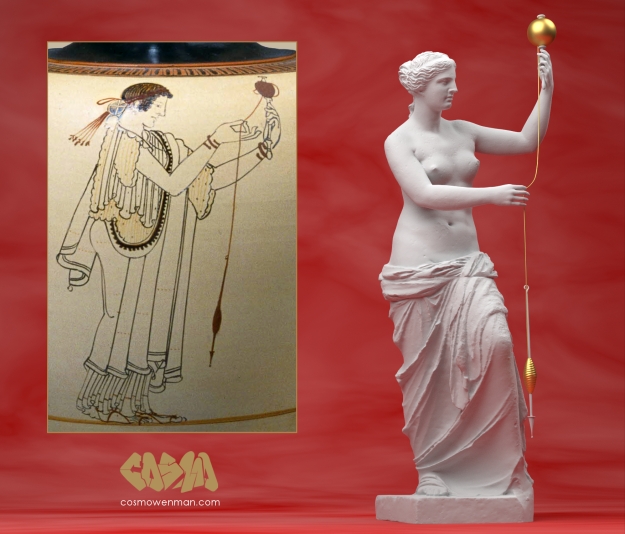

Venus de Milo, 130 BCE

1850 plaster cast by the Louvre atelier, 3D captured in the Skulpturhalle Basel museum 9/2013

This print of Venus de Milo is derived from my recent 3D capture of the Skulpturhalle Basel museum’s 1850 plaster cast of the original. That high quality cast, likely made by the Louvre’s own atelier, was part of a vibrant 19th century tradition of museums, universities, art schools, and wealthy collectors buying and trading plaster reproductions of famous works from each other so that they could be seen by larger audiences. That tradition is about to be brought back to life — when I publish my 3D capture and 3D printable files of Venus de Milo, anyone will be able to print their own copy.

Materials: PLA plastic with patinated copper finish

.

Winged Victory of Samothrace, 200 BCE

1892 plaster cast by the Louvre atelier, 3D captured in the Skulpturhalle Basel museum 9/2013

This print of Nike, Winged Victory of Samothrace is derived from my recent 3D capture of the Skulpturhalle Basel museum’s plaster cast of the original. That high quality cast was made by the Louvre atelier in 1892, and was one of the most popular plasters to be collected by museums, universities, art schools, and wealthy collectors around the world. Now that Winged Victory has been unveiled here as a 3D print, I will publish my 3D capture and 3D printable files, and she’ll be unleashed for everyone to enjoy.

Materials: PLA plastic with patinated copper finish

.

Getty Villa Caligula in Bronze, 40 AD

Marble original 3D captured at the Getty Villa, 11/2012

In early 2013, I produced a life-size bronze adaptation of my capture of the Getty Villa’s marble portrait of Caligula. In the onscreen design, I added a fracture to his neck to match that of the Met’s bronze portrait of his grandfather, Marcus Agrippa. I also deleted his eyes. When a bronze or marble has its eyes intact, the viewer can put themselves in the center of the sculpture’s field of view, as though it were looking back at them. The overall effect is proximity and familiarity. But when the eyes are lost, the piece never looks back. It is always looking through, or past, the observer. The subject becomes distant and enigmatic, even glamourous. Or perhaps dead, ghostly, or lost — a vacant, uninhabited shell of what once was, suggesting a previous life. It becomes an artifact.

Material: Bronze

.

Colossal Bust of Ramesses II / Ozymandias, 1250 BCE

Granite original 3D captured at the British Museum, 11/2012

I digitally cut away the damaged surfaces of my 3D capture of the British Museum’s famous Ramesses II, The Younger Memnon, the size, face, and incompleteness of which were the inspiration for Shelley’s Ozymandias. The pretty design is 3,200 years old, originally part of a mortuary temple in Thebes. All involved in its creation are long dead, unable to interfere with or protest its reuse and new life as data, plastic, or bronze. I printed and cast only the intact parts, creating a decorative bronze bauble, broken and patinated with age, worn bright where it has been touched.

Material: Bronze

.

“Ecstasy” by Eric Gill, 1910

Hoptonwood stone original 3D captured in the Tate Britain, 8/2012

“Death plus seventy years” is the magic spell that buries most art from the modern era along with its creators. Fortunately, if that’s the right way to put it, Eric Gill has been dead just long enough for all his work to have passed out of limbo and into the public domain. He’s been dead since 1940, so his work no longer has to be buried with him, or confined to a single place, instance, or iteration — or displayed in mausoleum-like museums. I captured Gill’s 1910 limestone Ecstasy at the Tate Britain in August 2012, and have given it a new life in bronze.

From Lost PLA Bronze Casting and the Art of the Living Dead

By Cosmo Wenman

Material: Bronze

.

Sketch of Perikles’ Helmet, 2nd century AD

Modelled after the original marble Portrait of Perikles 3D captured in the British Museum, 8/2012

I made a quick 3D capture of the British Museum’s Marble portrait bust of Perikles. I used the results as a template, taking its measurements and contours as a guide in order to design this rough 3D printed sketch of his helmet, making a copy of an artifact that has never been discovered.

Materials: PLA plastic with patinated bronze and brass finish.

.

“Georges Méliès” by Renato Carvillani, 1951

“Créateur du spectacle cinématographique”

Bronze original 3D captured in Père Lachaise Cemetery, 11/2012

I scanned several graves in Père Lachaise cemetery, Paris, in October, 2012. There are so many incredible sculptures to choose from there, monuments to incredible people. This one is special — the verdigris bronze bust by Renato Carvillani that graces the grave of French illusionist and cinematography pioneer Georges Méliès — the father of special effects and science fiction movies. It seems fitting to render him in a new medium.

Materials: PLA plastic with patinated bronze finish.

.

These pieces will be on display at Autodesk’s exhibit:

The Inopos / Alexander the Great, circa 100 BCE

Marble original 3D captured at the Louvre, 11/2012

Originally thought to represent the Cycladic river god Inopos, the nearly one meter tall fragmented bust known as “The Inopos” is now accepted as a portrait of Alexander the Great. If the full figure had survived intact, it would stand at well over eight feet tall—god scale. At the Louvre, the imposing, larger-than-life figure hides in plain sight, largely unnoticed, staring down at the crowds that flock to see the Venus de Milo just twenty feet away.

I captured the original in the Louvre in October 2012 and digitally restored its damaged nose using a nose I captured from a portrait of Alexander at the British Museum.

From 3D Printed Portraiture: Past, Present, and Future

By Cosmo Wenman

Materials: PLA plastic with patinated bronze finish.

.

Head of a Horse of Selene, from the Parthenon, 438-432 BCE

Marble original 3D captured at the British Museum, 8/2012

I originally printed this horse and finished it in metal, in an effort to show that consumer-grade 3D printers can produce objects of art worthy of display. I made it life-size because I thought doing so would be jarring; it would help break consumer-grade 3D printing out of the toy and trinket realm and make it all seem more real somehow.

But I chose this and a few other archetypical subjects (like Alexander the Great) in particular to try to advance the idea that with 3D scanning and 3D printing, private collectors and museums have an opportunity to turn their collections into living engines of cultural creation. They can digitize their three-dimensional collections and project them outward into the public realm to be adapted, multiplied, and remixed.

If I can do it with just a camera and some free software, the Getty, the Met, the British Museum, or the Louvre–or a wealthy collector–can do it too. In fact, they’ve already done a lot of the scanning, they just haven’t done much of the publishing. But they should, in my opinion, because these technologies offer a way to break great art out of mausoleum-like settings, and put them where they can come alive and reach and influence many more people, in a vibrant, lively, and anarchic popular culture.

Materials: PLA plastic with patinated brass finish.

.

KNMER 406

KNMER 406